Are we really a nation of wealthy misers, or is there something more complex at play?

By Antonia Ruffell

Are Australians missing the mark in philanthropy compared to the US? The recent 2024 Annual Letter from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation urges philanthropists everywhere to step up in the face of huge global challenges like poverty and health crises. Reading the letter got me thinking about the role and potential of Australian philanthropy. We often hear that our giving lags the rest of the world. What’s more, our wealthy are getting richer while philanthropy declines and the chasm between rich and poor is growing.

This disparity raises critical questions: Why does Australia’s culture of giving differ? Are we really a nation of wealthy misers, or is there something more complex at play? And is there potential for wealthy Australians to play a bigger role in philanthropy moving forward?

US philanthropy outshines Australia

Despite a slight decline in 2022, US charitable giving remains impressive, totalling $499.33 billion according to the Giving USA report. This figure is boosted by the 735 American billionaires. The top 10 charitable gifts announced in 2022 totalled nearly $9.3 billion, according to The Chronicle of Philanthropy. Gifts from donors like Bill Gates, MacKenzie Scott, Steve Ballmer, Warren Buffett and others are having transformational impacts. In America, the rich give, give big, and give publicly.

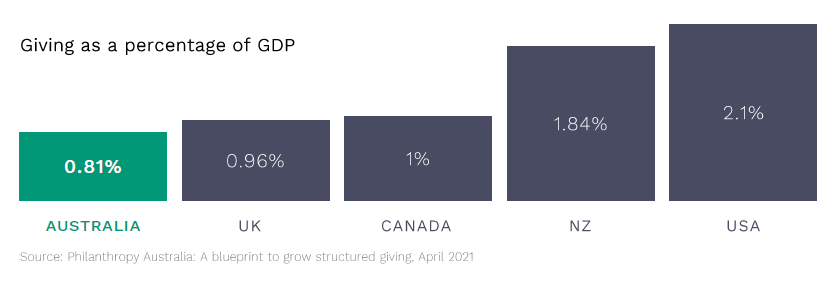

In contrast, Australia’s giving rates are lower. Centre for Social Impact research shows that donations by Australians are estimated to make up 0.81% of gross domestic product (GDP), compared to 2.1% in the US. While the wealth of Australia’s richest citizens has doubled in the last five years, giving from that group has stagnated. The average high-net-worth individual here allocates less than 1% to charity.

It isn’t all apples for apples – there’s differences in data, but that’s not all that is happening

Some differences exist between what the US and Australia count in their data as charitable giving. The US includes religious giving and giving to public schools within its charitable giving figures. The highest aggregate dollar amounts are donated to organisations focused on religion (32%), basic needs (20%) and education (16%, combining K-12 and higher education), according to the 2021 Bank of America Study of Philanthropy: Charitable Giving by Affluent Households. Meanwhile, in Australia, giving directly to churches or public schools to support their basic needs is not tax deductible and, therefore, not counted in our charitable giving statistics.

However, data aside, the difference in culture around giving is indisputable. Anyone who has spent time in the US can attest to how charity involvement is a source of personal pride, and happily spoken about. In fact, many would argue you’re a social pariah in wealthy circles if you can’t authentically talk about your charitable activities and philanthropy.

Cultural quirks matter: US versus Australia

The culture of philanthropy in the US has deep historical roots, dating back to the 1600s with the establishment of Harvard College and with the legacy of icons like Andrew Carnegie, John D Rockefeller, and the Ford Foundation. Fast forward to today, and this tradition is upheld from billionaires who subscribe to the Giving Pledge, promising to donate most of their wealth to philanthropic causes, through to everyday givers.

In the US, generosity is woven into the very notion of the American Dream. Giving in all forms is celebrated and expected, especially if you are successful. Research from GivingTuesday backs this up, showing that three-quarters of Americans enjoy giving and feel a responsibility to help others. Philanthropy is loud and proud, embedded in the nation’s social fabric.

In Australia, there is a sense that philanthropy is done privately and quietly. Charitable acts tend to be more understated. There’s a cultural quirk, where we are all for cheering on success, but not too loudly. It’s an intriguing mix of wanting to keep things fair for everyone – good old Aussie battler egalitarianism – but also not wanting anyone to get too big for their boots, the ‘tall poppy syndrome.’ People readily talk about house prices, their latest investment, or the kids’ private school. But philanthropic acts? There’s a tendency to view them with a hint of scepticism. This means that Australians are less vocal about our giving and there’s less societal pressure to give, potentially leading to missed opportunities to build a stronger philanthropic culture.

Tax incentives are strong – but an inheritance tax would be a gamechanger

The US’s slim social safety net fuels its giving culture, driving the wealthy to fill the gaps in public services. In stark contrast, Australia’s robust welfare system, complete with accessible education and healthcare, can lead to a sense that ‘it’s the government’s job to fix it.’

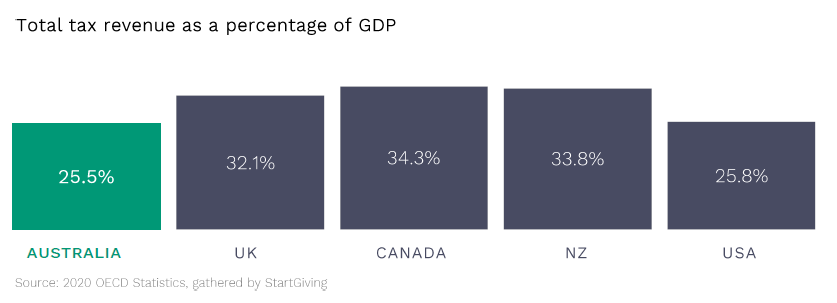

Despite perceptions, Australia isn’t a high-tax country. Our tax-to-GDP ratio is on par with the US and lower than that of the UK, Canada, and New Zealand – all countries with higher giving rates.

Australia’s tax incentives for philanthropy are strong. Donations to deductible gift-recipient charities are tax deductible – and structures like a private ancillary fund (PAF) or public ancillary fund (PuAF) offer tax-effective options for the wealthy to contribute significant amounts to charity. However, a notable absence in Australia’s tax system is an inheritance tax.

Australia is one of just eight developed countries that do not tax inherited wealth, after Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser abolished federal death duties in 1979. This is a contributing factor to why the wealthy do not give as much as in countries with inheritance taxes. In the US, leaving charitable bequests can substantially reduce estate tax burdens, a factor that has been shown to significantly influence giving behaviours. Researchers from the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center found that if the US abolished death duties, levels of bequests would fall by about a third (between 22% and 37%) and lifetime giving would be reduced by a similar amount.

Australia is at a crossroads, with the Productivity Commission Philanthropy Inquiry putting forwards a series of reforms to increase giving, including superannuation bequests, and even a proposed increase to minimum distribution rates for PAFs. However, the reintroduction of an inheritance tax –with an estimated $224 billion a year expected to be given in inheritances by 2050 – could be a game-changer for the Australian community. Unfortunately, it seems unlikely to ever get up given how challenging it would be for any governing party to sell it to the electorate.

The art of the ask: fundraisers and advisers could be better and bolder

In the US, the art of ‘making the ask’ is well-established. There’s a long-standing and proactive culture of fundraising. Non-profits often employ many staff dedicated to fundraising activities and donor relations – and there’s a clear expectation that board members not only govern but also contribute to fundraising efforts.

Australians, in contrast, have traditionally been more reserved in their approach to fundraising. While this is changing, with more charities recognising the need to invest in professionals who can navigate the complexities of donor engagement and gift solicitation, there is still a tendency to be less direct or aggressive in soliciting major gifts.

Additionally, in the US, it is common practice for financial professionals to discuss charitable giving as a core component of wealth management, tax planning, and estate planning strategies. This ensures that philanthropy is not just an afterthought but a core element of financial planning for many Americans.

In Australia, while there is a growing awareness of philanthropy in financial planning, the practice is not as widespread. Australian financial advisers are beginning to recognise the importance of including philanthropic conversations in their client interactions, but it’s an area ripe for development.

It isn’t all rosy – we can learn from critiques of US philanthropy

While Australia can draw valuable lessons from the American philanthropy, it isn’t all perfect.

Publications like Anand Giridharadanas’s Winners Take All warn that the super-rich elite, in trying to fix the world’s problems, risk keeping things the same, rather than driving long-term systemic change. Caution is required when too much power sits in the hands of a few. A movement of trust-based philanthropy, where donors collaborate closely with communities to identify needs and solutions, rather than imposing their own agendas, is growing in part to counter this criticism.

In Australia, we have an opportunity to learn from these critiques as our giving culture evolves.

There’s opportunity ahead and hope for the future

A new generation of Australian entrepreneurs, particularly in the tech sector, is showing a growing interest in philanthropy. Their approach is slightly different. As innovators, they are keen to know how and where their giving can be most effective. In his letter, Gates Foundation CEO Mark Suzman asks for “more urgency, more resources, and more bold, new ideas from around the world.” I am optimistic that Australia’s emerging philanthropists are ready to step up to meet this challenge – that progress is happening and giving when you’re successful will increasingly be the expected norm.

“Philanthropists all over the world are finding new ways to give to reduce inequities.

I hope they’ll do more, and that more people step up to join them.”

Mark Suzman, CEO, Gates Foundation